Understanding and Preventing Race Conditions in Web Applications

This article aims to correct a subtle but dangerous bad practice that is often overlooked. I will demonstrate practical examples using Python, FastAPI and PostgreSQL, and I will provide various solutions for the problem, each with its own trade-offs. I will role-play as a junior freelance developer, making it easier to understand the chain of thought.

The following code is unsafe: can you spot why?

class BuyItemRequest(BaseModel):

item_id: int

@app.post("/buy_item")

async def buy_item(

request: BuyItemRequest,

user_id: int = Depends(get_user_from_jwt),

):

item = await Item.get(id=request.item_id)

user = await User.get(id=user_id)

if user.money < item.cost:

return {"error": "Not enough money to buy item"}

user.money -= item.cost

await user.save(update_only=["money"])

# successfully bought. TODO: add product in the database

...

return {"bought": bought}What is a race condition, anyway?

Read here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Race_condition

A race condition occurs when two or more operations compete to access shared resources in an unpredictable order, potentially leading to unexpected and erroneous results. It’s like multiple runners racing towards a finish line, where the outcome depends on who gets there first.

The main takeaway is that race conditions can cause data corruption, crashes, or security vulnerabilities.

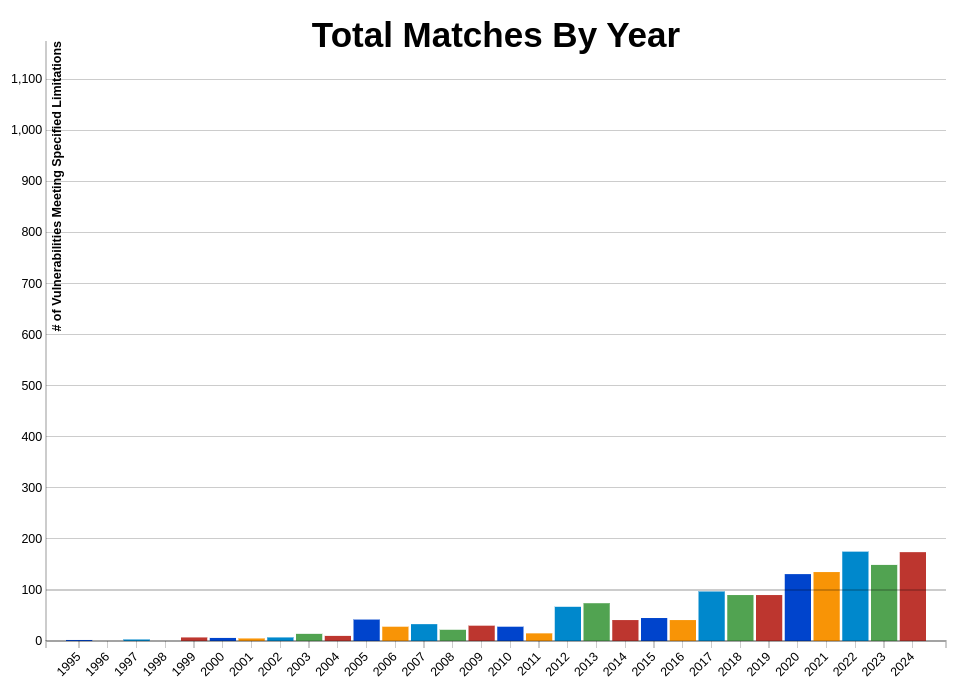

As a matter of fact, there have been more than 174 vulnerabilities reported in 2024 alone, with some of them being of high severity (source: NIST)

First case: blog views

A small company asked me to create a custom CMS website for their blog. They also want to know how many times an article has been viewed in total.

NOTE: I am omitting the boilerplate parts of the code for the sake of demonstration. The full code is available on my GitHub and it’s linked in the end.

Let’s start by defining our database model. I am using tortoise-orm as my ORM of choice. It will automatically generate the SQL for us. The code will be written in worker.py.

class Post(Model):

id = fields.IntField(pk=True)

title = fields.CharField(max_length=255)

content = fields.TextField(max_length=4096)

views = fields.BigIntField(default=0)

class Meta:

table = "posts"Next, let’s create a simple REST API:

- Create a database connection and insert a default blog post with

id=1 /post/<post id>will return the post’s content and metadata/view/<post id>will increase the post’s views by one

# ... omitted boilerplate

app = FastAPI(lifespan=lifespan, debug=True)

@app.get("/post/{post_id}")

async def get_post(post_id: int):

post = await Post.get(id=post_id)

return {

"post_id": post.id,

"title": post.title,

"content": post.content,

"views": post.views,

}

@app.post("/view/{post_id}")

async def view_post(post_id: int):

# UNSAFE!! Do not use this in production

post = await Post.get(id=post_id)

post.views += 1

await post.save(update_fields=["views"])

return {"current_views": post.views}Generated SQL Queries

SELECT "content","title","id","views" FROM "post" WHERE "id"=1 LIMIT 2 UPDATE "post" SET "views"=1 WHERE "id"=1

Note: the LIMIT 2 is generated by the ORM to check against multiple results in a .get() operation expecting only a single element.

So far so good. Let’s test our code!

$ curl -X GET 'http://127.0.0.1:8000/post/1'

{"post_id":1,"title":"Example blog post","content":"Hello! This is a blog post","views":0}Nice, the post has 0 views. Let’s try to increase them and fetch the post again.

$ curl -X POST 'http://127.0.0.1:8000/view/1'

{"current_views":1}

$ curl -X POST 'http://127.0.0.1:8000/view/1'

{"current_views":2}

$ curl -X POST 'http://127.0.0.1:8000/view/1'

{"current_views":3}

$ curl -X GET 'http://127.0.0.1:8000/post/1'

{"post_id":1,"title":"Example blog post","content":"Hello! This is a blog post","views":3}Great! It seems to be working perfectly, doesn’t it? The view count increases with each request, and we can retrieve the updated post with the correct number of views. Everything appears to be in order… right?

…right?

I was happy, yet another side gig has been completed, and I delivered the project in time. Let’s call it a day, I told myself.

Until, the following day the company that asked me to make the website called. They said that despite millions of visitors after the initial release, the views counter is reporting a few tens of thousands at most.

As my enthusiasm crumbles down, I try to think of a possible cause. So I begin troubleshooting. I remembered that the company told me that the page has been swarmed with visitors from the very moment it came online. This means that a lot of requests were made at the same time. So I try to test this theory by myself, by creating a script.

In [1]: import asyncio

In [2]: import httpx

In [3]: async def get_views():

...: async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

...: r = await client.get("http://127.0.0.1:8000/post/1")

...: return r.json()["views"]

...:

In [4]: async def view_post():

...: async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

...: await client.post("http://127.0.0.1:8000/view/1")

...:

In [5]: await get_views()

Out[5]: 8

In [6]: _ = await asyncio.gather(*[view_post() for i in range(100)])

In [7]: await get_views()

Out[7]: 10The script is supposed to send 100 concurrent requests to the API at once. I fetched the views before and after making 100 requests, and I noticed that the difference is just 2, instead of 100. Bingo!

As I search for a solution online I stumble on an old answer from a forum, telling me to “lock the record row-wise with SELECT FOR UPDATE”. It makes sense, I remember learning locks in my classes, so I assume databases must have a similar built-in function.

Without wasting a second, I update my code:

@app.post("/view/{post_id}")

async def view_post(post_id: int):

# UNSAFE!! Do not use this in production

post = await Post.filter(id=post_id).select_for_update().get()

post.views += 1

await post.save(update_fields=["views"])

return {"current_views": post.views}Generated SQL Queries

SELECT "views","title","id","content" FROM "post" WHERE "id"=1 LIMIT 2 FOR UPDATE UPDATE "post" SET "views"=2 WHERE "id"=1

And test it again:

In [10]: await get_views()

Out[10]: 1

In [11]: _ = await asyncio.gather(*[view_post() for i in range(100)])

In [12]: await get_views()

Out[12]: 12Wait, what? Even locking the row doesn’t work… Or does it? After some troubleshooting, I realized that something was amiss.

After asking for help to a friend, he tells me I am missing a transaction.

@app.post("/view/{post_id}")

async def view_post(post_id: int):

async with in_transaction():

post = await Post.filter(id=post_id).select_for_update().get()

post.views += 1

await post.save(update_fields=["views"])

return {"current_views": post.views}Generated SQL Queries

DEGIN SELECT "views","id","content","title" FROM "post" WHERE "id"=1 LIMIT 2 FOR UPDATE UPDATE "post" SET "views"=1 WHERE "id"=1 COMMIT

Code updated, testing begins again.

In [1]: await get_views()

Out[1]: 0 # yes, I had to reset my local database

In [2]: _ = await asyncio.gather(*[view_post() for i in range(100)])

In [3]: await get_views()

Out[3]: 100

In [4]: _ = await asyncio.gather(*[view_post() for i in range(1000)])

In [5]: await get_views()

Out[5]: 1100NOTE: This works because the two queries are executed inside the same transaction. When selecting

FOR UPDATE, the row is locked for the whole duration of the transaction. Earlier,tortoise-ormwas probably ending a transaction instantly after selecting the row, therefore unlocking it.

Hurrah! It works. I even tried to simulate 1000 concurrent requests. I shipped the code to production without hesitating, and I notify the company, which is happy to hear I fixed the issue.

Or have I?

Another day, another call. “What is it, now?”, I think to myself before answering. They told me that the site is being very slow, the request for updating the view counter is hanging for most users.

I make an attempt at figuring out what’s wrong. Every time the /view/<post id> endpoint is called, the row is being locked until the transaction ends. Analogously, it’s as if all the requests towards that endpoint get queued one by one. Computers are fast, but locking and unlocking a mutex is a very expensive operation.

TIP: Namely, the following line of code is waiting for the row to get unlocked before being able to select it. This is the cause of the delays. Concurrency is impaired because of this very bottleneck.

...

async with in_transaction():

post = await Post.filter(id=post_id).select_for_update().get()Once again, I try to look for a solution.

After a simple search of “ways to avoid select for update incrementing counter”, this StackOverflow answer comes up.

The correct SQL Query should be atomic, as in it should update the value atomically. Simply put, it means that adding one actually adds one to the value, in practice.

TIP: The

UPDATEstatement is atomic by nature. It performs the read and write operations in a single, indivisible step. This eliminates the need for explicit row-level locking. This approach scales much better under high concurrency, as it doesn’t hold locks for extended periods.

UPDATE TABLE posts

SET views = views + 1

WHERE post_id = $1

RETURNING views;

-- $1 is a placeholder for the actual post_id valueThe aforementioned logic, can then be translated into Python code as following:

@app.post("/view/{post_id}")

async def view_post(post_id: int):

await Post.filter(id=post_id).update(views=F("views") + 1)

post = await Post.filter(id=post_id).get()

return {"current_views": post.views}NOTE: Note: in tortoise-orm there is currently no way to add a

RETURNINGstatement, this is why I am fetching the value twice. This is of course highly inefficient, but it’s alright for demonstrative purposes. Ironically, there is a race condition with this very approach, where the updated value after theUPDATEstatement might not match with the one obtained later with.get(). In this case, it’s not really a problem, as it would return the most recently updatedviewsvalue anyway.

WARNING: Oh, and by the way, the code doesn’t account for invalid post ids. Be careful.

Second case: a game shop

Let’s step up the game (pun intended) by adding another constraint to our riddle.

Assume that you are working on a game. It is possible to buy level upgrades, only if the player has enough coins. This means that the balance must never reach below zero.

Let’s define our model:

class Player(Model):

id = fields.IntField(pk=True)

name = fields.CharField(max_length=255)

money = fields.IntField(default=0)

level = fields.IntField(default=1)

class Meta:

table = "players"We will also create a dummy player, Alice, on startup:

await Player.create(id=1, name="Alice", money=1000, level=1)And after learning our previous lessons, we write the following endpoint:

COST = 150

@app.post("/upgrade/{player_id}")

async def upgrade_level(player_id: int):

# Slow, but safe

# row level locking

async with in_transaction() as conn:

player = await Player.filter(id=player_id).select_for_update().get()

if player.money < COST:

return {"error": "Not enough money"}

await Player.filter(id=player.id).update(

level=F("level") + 1,

money=F("money") - COST,

)

await player.refresh_from_db()

return {"user_id": player.id, "money": player.money, "level": player.level}Although slow, it is completely free from race conditions. But what if we wanted the best of both worlds: safe AND fast?

Sure enough, there are multiple ways.

We could write the following atomic

UPDATEquery:UPDATE players p SET money = money - $1, level = level + 1 WHERE p.money >= $1 RETURNING p; -- $1 is replaced with the COST variable in the queryIt would translate to the following Python code:

@app.post("/upgrade/{player_id}") async def upgrade_level(player_id: int): # Fast and safe rows_updated = await Player.filter( id=player_id, money__gte=COST, # gte = greater than or equal ).update( level=F("level") + 1, money=F("money") - COST, ) if rows_updated == 0: return {"error": "Not enough money"} player = await Player.get(id=player_id) return {"user_id": player.id, "money": player.money, "level": player.level}IMPORTANT: Important: in your real application the endpoint must be authenticated. It is a really bad practice to allow any user to pass an arbitrary, unsanitized, id to your API.

Database-level constraints: PostgreSQL offers the possibility to add constraints to your columns. We could write our

CREATEstatement as such:CREATE TABLE posts ( id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY, title TEXT, content TEXT, views INTEGER CHECK (views >= 0), );Or alternatively,

ALTERan existing table:ALTER TABLE posts ADD CONSTRAINT check_views_non_negative CHECK (views >= 0);This ensures that any write operation that sets the

viewsfield to a value lesser than 0 will fail at the database-level, throwing an error.

Further reading

Transactions do not inherently prevent all race conditions. Do not live under the false presumption that they do, or it could result in catastrophic errors.

I recommend reading the following answer: https://stackoverflow.com/a/26081833/13673785

Transaction Isolation

https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/transaction-iso.html

PostgreSQL anti-patterns: read-modify-write cycles

In depth explanation of avoiding race conditions in PostgreSQL. It also covers:

SERIALIZABLEtransactionsOptimistic concurrency control

https://www.2ndquadrant.com/en/blog/postgresql-anti-patterns-read-modify-write-cycles/

Oh, and by the way, you might find online solutions suggesting to use LOCK TABLE. It is a terrible idea.

NOTE: Sure, a software-side Mutex could be used, but it won’t protect you when you have multiple instances of your application running. It’s a good idea to use a database-level lock, as it will work across all instances of your application, and it can be used in a distributed environment as well.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how easily race conditions can sneak into our code, and how tricky they can be to squash. From simple views counters to game economies, we’ve explored practical solutions like atomic updates and database constraints.

The key takeaway? Always think about concurrency, even when it’s not obvious. Test rigorously, and don’t assume your database operations are safe by default.

Remember, there’s no silver bullet. Each solution has its own trade-offs. Choose wisely based on your specific needs.